Times’ cycle safety campaign puts danger centre stage

Times’ cycle safety campaign puts danger centre stage

In the wake of the Times’ Cities Safe for Cycling campaign, there has been little filling the newspapers and bouncing around the corridors of social media than talk of cycling danger. Rather than encourage more people to get out on their bikes – presumably one of the long-term goals of the Times’ campaign – it has done plenty to reinforce the image of cycling as a daring exploit, only undertaken by the truly mad, bad or dangerous to know. Things got even worse when David Cameron decided to describe cycling UK city roads as “taking your life into your hands.” That’s the same David Cameron who thought that cycling into Parliament was a great photo call back in 2006. Likewise, the tagline “Save our Cyclists”, mimicking the sailor’s distress call is evocative, but unlikely to make wavering would-be-cyclists go out and buy a bike. The campaign was conceived as a result of the serious injury to Times’ journalist, Mary Bowers, so the emphasis on safety is understandable. But surely the overall point is to help more people ride bikes? But exactly how dangerous is cycling on the roads of the UK?

Is cycling dangerous?

Is cycling dangerous?

As with anything subject – anecdotal evidence abounds. Everyone knows someone who has had an accident on a bicycle, therefore it must be dangerous. Likewise, most of us will know someone who has had an accident in a car but for some reason we are more likely to move on and accept that as an unfortunate fact of life, unlike cycling accidents. Many campaigners and commentators have come out in the past few weeks, indignant about the cycle safety situation on the nation’s roads, citing first-hand experience to back themselves up. However, to get an unbiased, bird’s eye view of the situation we should turn to the not so compelling, less than glamorous, but sound and increasingly consistent body of research.

How dangerous is cycling compared to other activities?

The other day I read a letter in the Metro in which the writer voiced his opinion that anyone who took greater risks should pay more for the NHS. He gave examples of the obese, habitual drunks and even skiers. I wondered if he thought cyclists should be included on that list. So, how does cycling compare with other activities that we take part in regularly, without a second thought for safety? A UK study, admittedly based on data collected in the 1980s, shows that those taking part in tennis or football were statistically more likely to die than people riding bikes. Even more hazardous was swimming, shown to be seven times more likely to result in an untimely death. With the increases in road traffic since the 80s, cycling may have become a bit more dangerous but it is unlikely to be the daring, “life in your hands” pursuit depicted by the Prime Minister. A similar study in the more car-orientated US, this time based on information collected in the 1990s, looked at the risk of death across a range of activities per million hours. So, this took into account the fact that people usually spend a lot more time in a car than riding a bike. Once again swimming turned out to be a more deadly activity, as did traveling by car. Frequent flyers can relax though, as going in a plane was safe by comparison. So, cycling may not be quite as dangerous as we perceive.

Do I really need to wear a cycle helmet?

Do I really need to wear a cycle helmet?

The other great cycle safety debate hinges around whether riders should wear a helmet. In the UK we have gone from the 80s, when barely anyone wore a helmet (who remembers the Tuff Top?), to today where, at a guess, at least 50% of cyclists are wearing head protection. Common sense and some robust research have shown that, in the event of hitting your head, a cycle helmet offers you protection. Of course – a helmet is better than nothing. But we have to remember what cycle helmets were designed for. In order to comply with safety standards in the UK, helmets must be protective in the event of a vertical fall from one metre on to tarmac. They are designed for falling of a bike. Full stop. Nothing else. They make no claims to be effective in collisions with cars. So every time a newspaper concludes a report of a road accident involving a bike with the phrase “the cyclist was not wearing a helmet” it enforces the misconception that a helmet may have helped.

Do people drive closer to you if you wear a helmet?

Another reason that helmets may not be the safety panacea they have often been painted is that wearing one also changes other people’s behaviour towards you – particularly drivers’. A 2006 study from the University of Bath demonstrated that when a cyclist wears a helmet, drivers are more likely pass within one metre of them, increasing the chances of a collision. The study only collected information on one cyclist around the Bath area (although it included data on the interactions with more than 2,000 vehicles) but it does suggest that the case for wearing a helmet is not so clear cut.

Does obliging people to wear helmets save lives?

Does obliging people to wear helmets save lives?

Adding to the ambiguity are larger pieces of research looking at the bigger picture. A 2006 review, published in the British Medical Journal, examined data cycle accidents in regions in Australia, New Zealand and Canada where helmet use had been made compulsory. The research found that while helmet use had increased massively, as you’d expect, the legislation had no effect on the number of bicycle accidents which resulted in a head injury. Helmets alone, in the event of a low speed collision, have been proven to give your head greater protection. So the overall picture must be more complicated. Another often cited theory is that cyclist who wear helmets, feeling more secure and confident with their protective headgear, are more prone to taking risks. However, there appears to be no solid research that proves this either way.

Cycle helmet law for the UK?

In response to the spotlight on cycle safety, several politicians have raised the issue of a law to enforce the use of cycle helmets in the UK. Even before the current focus on cycling, the WI had been considering adopting the promotion of a helmet use law as the centrepiece of their campaigning for the coming year. Let’s hope they take a close look at the research before pressing ahead. So, to sum up – bicycle helmets protect your head in the right situation but their use may change the behaviour of drivers, and possibly cyclists, cancelling out their beneficial effects. Not to mention discouraging large numbers of people from cycling, be it through perceiving it as dangerous or not wanting to mess up their hair. There’s no experimental data on the latter but I think I have all the anecdotal evidence I need.

Turning around cycling’s dangerous image

Turning around cycling’s dangerous image

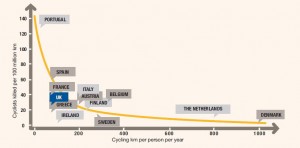

The current discussion around cycle safety is healthy, especially considering that cycling has been shown to be much more dangerous in the UK than in many countries on the continent, but it has to be considered in context. It’s also more dangerous to drive in the UK than it is in Malta or Iceland but we are not thinking of importing road traffic policy wholesale from those countries. As well as a focus on safety and investment in infrastructure, what cycling really needs is to shake off its dangerous image. People need to see all the positives in cycling – and there are many. It keeps you fit and healthy. It helps you loose weight. It’s better for the environment. It’s cheap. It’s convenient. And, above all, it’s fun. Children are a pretty good barometer of what is fun – and kids love their bikes. The feeling of balancing with the wind in your hair might lose its thrill a little as the years go by, but who doesn’t love whizzing down a hill and maybe jumping neatly off the curb? The parliamentary debate on 22nd February did touch on “the joy of cycling” but this was framed within a much larger, gloomy, safety-focused debate.

Getting more people on bikes will make cycling safer for all

Convincing people that cycling is fun and safe will serve to encourage more people to get cycling – a key ingredient for making riding bikes safer on our roads. An international research study found that as the numbers of cyclists on the road increases, the likelihood that they will be involved in an accident decreases. This is not only due to their being fewer cars on the road – drivers’ attitudes and behaviour change as they see more cyclists around. This has already been shown to be the case in the UK. In the decade following the 1973 oil crisis cycle traffic increased by 70%, while over the same period the fatality rate per cyclist fell 50%. It’s the critical mass argument in practice. Cycling becomes normalised, people begin to believe that cyclists have a right to be on the road, not just cars. At the moment cyclists are an annoying minority to most motorists. Irrelevant at best. Sheer volume will change attitudes but that won’t happen without more people taking up cycling. More cyclists will mean that more drivers are also cyclists and vice versa which will increase understanding on the roads. And experience is really a very powerful tool. Many HGV and bus drivers are now being asked to take cycling awareness training which involves getting on a bike and cycling in traffic with an instructor. Having first-hand experience of what it feels like to have a lorry a few metres behind you, revving its engine, with traffic trying to squeeze past, can really hit home.

Gaining confidence on a bike

Gaining confidence on a bike

I am not afraid of cycling and have happily cycled to and from work in London, Bristol and several other cities over the years, often along busy roads. But, the thing is I grew up in a small village riding bikes all day every day. I am at ease, comfortable and balance on a bike – and I had a lot of opportunity as a child in a safe environment to get that experience. That’s not to say I haven’t had a few falls. A couple of months ago I w as on my way to the train station and a cyclist came unexpectedly around a blind corner, I misjudged a curb and went flying over the handlebars. Any injuries? Not even a graze I was surprised to find. A look across the press in recent days would give you the impression – especially if you had never ridden a bike – that every cycle accident was fatal. Far from it, more than 8 out of 10 cycle accidents end with only very minor injuries – a few cuts and bruises. Unfortunately, not everyone grows up with the opportunity to cycle as much as I did.

Persuading people to cycle

A review of interventions to promote cycling, carried out by the Institute of Education, found that campaigns that promoted cycling as a healthy and convenient method of transport, alongside infrastructure improvements, were the most likely to be successful in boosting cycling numbers. Even if they choose not to cycle, most people understand that riding a bike i s a healthy pastime. But not so many really appreciate how convenient it can be. A journey that would take an hour on two buses with a change in the middle becomes a 15 minute bike ride. You can turn the walk to the local shop from a 20-minute round trip to five minutes, there and back. The problem is that these benefits are not obvious until you have got used to riding a bike and learn your way around your local area. The review of campaigns to get people cycling also discovered the improving infrastructure was particularly important for encouraging children to take up cycling. This ties in with the fact that one the key fears parents have for their children is safety – so traffic free path means they will allow their children to cycle. This is great news, as today’s cycling children will be the adults who ride to work in the future.

Cycle training

As well as improving infrastructure, cycling lessons are surely a key way to build people’s confidence and the likelihood they will integrate cycling into their daily lives. We used to call it cycling proficiency when I was at school, now it’s Bikeability, but it amounts to the same thing – giving young people confidence on bikes and helping them learn the rules of the road. It’s great that you can even do these as an adult these days – so it’s not too late for anyone. Not only should the Government be encouraging and funding schemes like this, but private companies that can afford it should consider putting this in alongside a Cycle to Work Scheme. Parents too need to take responsibility by allowing and accompanying their children on their bikes. I have no research to support it, but I’ll bet the child of a cyclist is far more likely to become a regular cyclist themselves. As well as getting people to perceive cycling as safe, it would also help if it was considered as a bit cooler. It’s got a lot more mainstream in the past few years – thanks to huge efforts by campaign groups, some top British athletes endorsing cycle training and some trendy single speeds – but it still hasn’t quite lost the sweaty Lycra badge. Why can’t we all effortlessly cycle around in our normal clothes as they seem to manage so well in Amsterdam? Surely it can‘t all be down to the hills.

Overcome your fears and ride a bicycle!

If you’re afraid of cycling, remember it’s really not that bad. If you aren’t out riding a bicycle because you are scared of having a fatal accident, then you should also consider giving up tennis and football too (but golf‘s OK). Walking down the street and driving in France are also out. When you look into the odds it starts to seem like an irrational fear. Don’t get me wrong, there are some dangerous sports out there where the risks are a lot higher than everyday life – base jumping, for example – but cycling is so within the bounds of everyday risk levels that it’s crazy to dismiss it. So get on your bike, get fit, save money and above all have some fun and stop worrying.

What do you think? Agree? Disagree? Got another point of view?

Please leave a comment below.